A Simple Framework for Thinking About Quasi-Binary Events

What is the Price of Asymmetry?

This is not a recommendation, a trade idea, or a forecast.

It is an attempt to explain how I think about uncertainty when outcomes are asymmetric, information is incomplete, and timelines are largely outside an investor’s control. If you are looking for buy or sell alerts, or something you can directly act on without context, this will likely disappoint you and that is intentional. What follows is a way of how I frame problems, not a set of instructions.

When people evaluate biotech or life science investments, particularly those tied to regulatory or clinical milestones, they tend to fixate on a a few questions: will it work? will it get approved? is it safe? is there a standard of care? And in the case of life sciences more broadly, what multiple will investors pay for growth? These questions feel intuitive, but I think it is the wrong place to start. Markets are generally decent at forming views about probability. They are much worse at pricing asymmetry — how much changes if something works versus how much is lost if it doesn’t.

I care less about whether success is guaranteed and far more about whether the payoff profile compensates for the uncertainty involved. An investment does not need to be likely to succeed to be interesting. It needs to be mispriced relative to its potential outcomes. Many biotech situations are dismissed not because success is impossible, but because certainty is unavailable. Markets tend to penalize ambiguity more than they should.

When I refer to a quasi-binary event, I am describing situations where the outcome space is narrow, the timing is uncertain, and the consequences of success or failure are highly asymmetric. Regulatory decisions often fall into this category. While the reality is rarely a clean yes or no (there are delays, partial wins, additional studies, and second-order effects) the market frequently prices these situations as if the future collapses into a single coin flip. That simplification is often where mispricing begins.

Another way to think about quasi-binary events is through the shape of the distribution rather than the headline probability. In many of these cases, the left tail is relatively well-defined. There is usually a finite amount you can lose, and downside scenarios tend to cluster around a small number of outcomes: delay, rejection, dilution, or incremental de-risking that fails to change the narrative. These outcomes can be painful, but they are often bounded and broadly understood by the market.

The right tail, by contrast, is frequently under-appreciated in biotech and life sciences. Positive outcomes can trigger nonlinear effects: forced re-underwriting and consensus updates, capital flows from liquidity providers who were previously structurally unable to participate, strategic optionality that was not priced in, or changes in time horizon that compress years of uncertainty into weeks or days. The market often treats these upside scenarios as improbable or irrelevant, even when their impact would be disproportionate. This asymmetry is why I focus less on point estimates and more on the distribution of outcomes. When the left tail is known and the right tail is ignored or discounted, the mean becomes misleading. The question is not whether success is the most likely result, but whether the market is systematically underweighting the magnitude of success if it occurs.

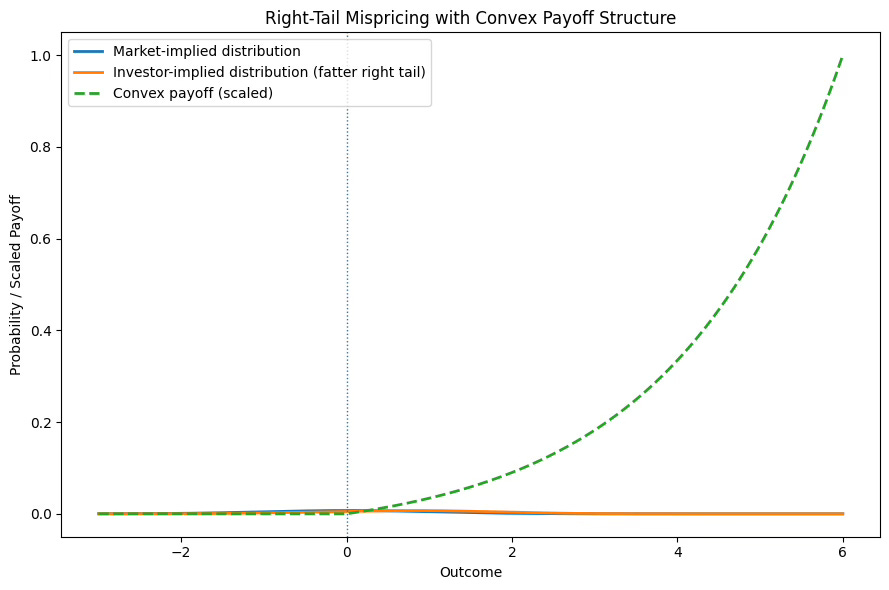

This is where the distributional framing matters. The figures below illustrate how mispricing emerges when outcome distributions are asymmetric and payoffs are convex. Markets often price assets using an implied probability distribution, Pm(x), that is relatively thin-tailed on the upside, effectively treating outcomes as near-binary. My internal view may assign greater weight to the right tail for two reasons. First, because I have insight into how outcomes would cascade if success occurs —regulatory decisions, capital allocation shifts, and time compression effects are nonlinear and difficult to price in advance. Second, in some cases the market may also underweight the probability of favorable outcomes themselves, particularly when complexity, institutional constraints, or unfamiliarity obscure evidence that meaningfully shifts the odds.

When payoffs are convex, expected value becomes highly sensitive to both the probability mass assigned to the right tail and the magnitude of outcomes within it. If the market discounts either (or both) it can systematically understate expected value, even when uncertainty remains high. The opportunity, therefore, does not always lie solely in the magnitude of the upside but also mispricing the probability of success itself. This can occur when complexity or institutional frictions lead investors to underweight evidence (ie. my internal view) that increases the likelihood of a favorable outcome. When both the probability of being right and the payoff conditional on being right are mispriced, the asymmetry compounds. These situations are rare and require humility, because overconfidence is an easy trap. However, when they arise, expected value can be meaningfully higher than what price implies, not because uncertainty disappears, but because both the odds and the consequences of success are misunderstood.

Figure 1*

*Differences in Pm(x) and Pi(x) occur when there is underweighting of right-tail outcomes AND underestimation of the probability of success

Figure 2

Before I ever think about sizing or timing, I try to answer a small set of questions. None of them are designed to predict the future with confidence. They are designed to understand whether the odds are skewed.

First, what is the payoff asymmetry? If things go right, what actually changes? Does the asset re-rate structurally, or is the upside dependent on fleeting sentiment? Is there durable value creation, or merely a temporary repricing? I am not interested in outcomes that require perfect execution and perfect market psychology at the same time.

Second, what is the market implicitly assuming? Every price embeds a narrative. Sometimes the market assumes approval is unlikely or maybe some life science company is a perpetual ‘shitco’. Sometimes it assumes timelines will stretch indefinitely, or that encouraging data is unreliable, or that optionality is not worth paying for, or that a randomized clinical trial is inevitable. I try to identify which assumption is doing the most work and whether it is reasonable given the evidence.

Third, where could this go wrong in a non-obvious way? This is the most important step. I want to be explicit about what would truly invalidate the thesis versus what would merely introduce noise or delay. Being wrong early is not the same as being wrong structurally, and confusing the two leads to poor decisions.

Finally, what does patience get paid? Time is not free, but it is often underpriced. In many quasi-binary situations, the market demands certainty immediately and penalizes anything that requires waiting. If the underlying thesis survives the passage of time, patience itself can become a source of return.

It is tempting to judge these situations purely by outcome, especially in retrospect. That instinct is understandable but it is also misleading. A good decision can lead to a bad outcome and a bad decision can get lucky. What matters is whether the process was sound given the information available at the time. This is why I care deeply about writing before outcomes are known and about timestamping my thinking. It forces intellectual honesty and helps separate luck from judgment. Over time, a consistent process matters far more than any single result.

This framework does not lend itself to buy or sell alerts, and I have no interest in pretending otherwise. Allocation, risk tolerance and time horizon are all personal. Copying trades without understanding context is a good way to learn the wrong lessons and take the wrong risks. What I try to offer instead is transparency around how I am thinking: what I am watching, what would change my mind, and where uncertainty still exists. That approach is less exciting in the short term, but far more useful over time.

Quasi-binary events are uncomfortable because they force you to live with ambiguity, and markets do not like ambiguity. Most people don’t either. But when uncertainty is unavoidable, the goal is not to eliminate it, the goal is to understand whether you are being compensated for bearing it.

Paid subscribers see how this framework translates into real allocation decisions, with timestamps and context.